James Leach has a line he uses whenever someone tells him that his son doesn’t look like he has Down’s Syndrome.

“Ah, it’s his off day,” Leach said with a laugh.

He and three other special needs parents discussed how to handle awkward situations like those and other challenges related to special needs parenting during a July 25 webinar hosted by Shield HealthCare, a medical supplies company serving caregivers and people living with medical conditions.

Though parenting was the topic, much of the conversation focused on how to survive being a special needs parent – a topic we Joubert Syndrome parents can always use to learn more about!

So below are some of the main pieces of advice from the panelists – Alethea Mshar, Dr. Liz Matheis, Jamie Sumner and James Leach. You can watch the hour-long webinar for free on Shield HealthCare’s website: www.shieldhealthcare.com/community/grow/2018/06/25/parenting-a-child-with-special-needs-roundtable-webinar/

Spoon Theory

The first lesson from the discussion: You’ve only got so much energy to go around – and you have to reserve some of it for yourself.

To make that job easier, panel moderator Alethea Mshar said that it helps to think about the amount of energy you have on any given day as a pile of spoons. As you use your energy, your spoons are taken away.

Thus, Mshar said, you should hold onto a few spoons for yourself. Her husband helps her with that task.

“He knows to shoo me out of the house so I can get a little bit of fresh air, get a little bit of exercise,” said Mshar, an author, blogger and regular contributor to the GROW with Shield HealthCare blog.

Dr. Liz Matheis said she often finds herself staying up late to get some time to herself – but then pays a price for that in the morning.

“I’m depleting myself of spoons while I’m trying to give myself spoons. It’s a hot mess,” said Dr. Matheis, a clinical psychologist who specializes in working with children with ADHD, anxiety, autism and other issues, in addition to having a child with special needs.

Jamie Sumner – who often doesn’t “even want to watch a challenging Netflix show” at night – gave a different perspective on going to bed early.

“An early bedtime is like sleeping in,” she said.

Ring Theory

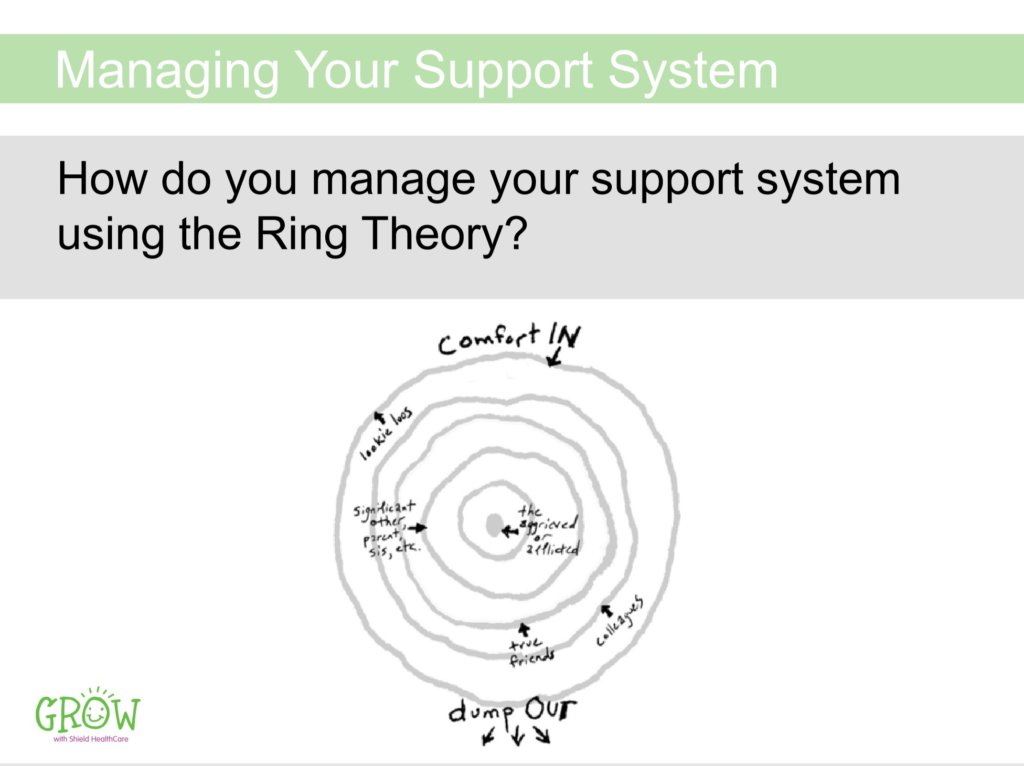

Mshar then brought up another concept called “ring theory.” It goes like this: The person dealing directly with an extremely difficult situation is at the center of a circle. Immediate family members make up the first ring around them, close friends are on the ring after that, followed by work colleagues and then more distant relatives and friends. The person in the middle of the ring can vent about the situation to anyone on any ring. But no one can vent about it to the person in the middle – or anyone closer to the middle.

It’s the “comfort in, dump out” rule, Mshar noted.

“They can’t vent to me about how they’re frustrated with my life and my child, or how they’re upset that my child is sick again,” she said.

Leach noted, however, that it’s hard to tell some people that they aren’t all that close to the center of the circle (which means they shouldn’t be dumping their concerns on the people who are).

Sumner said her diplomatic husband handles that task. She noted, however, that she isn’t comfortable venting about some problems to just anyone.

Dr. Matheis said she confides in her home therapist, who understands the situation she’s in.

“It’s really hard to find those people. … Unless you’re doing it, I don’t think anyone gets it,” she said.

Dealing with Guilt

Sumner’s son has a stander in their living room. Every time she sees it, she feels bad, like she hasn’t been using it enough.

And when the family decided to get him a power wheelchair, she felt guilty again, like they’d given up on getting him to the point where he could use a manual wheelchair.

To deal with that guilt, Sumner said she reminds herself that “the ultimate goal can’t be to push, push, push them in every way possible.”

Leach recommends focusing on the long term.

“We don’t have to be the best. We just have to be the best that we can be in that particular moment,” he said.

Making Comparisons

Like other panelists, Leach mentioned that it’s too easy for parents with special needs kids to compare them to typical kids.

Instead, he tries to compare his son Corbin to where he was in the past and “celebrate little wins” – even if it’s just eating a small amount of food without using his feeding tube.

Sumner said she sometimes even gets upset when she compares her special needs son to other special needs kids that seem to be making progress faster.

She tries to remember that her comparisons aren’t very accurate, given that she doesn’t know the other kids very well.

“The comparison never works because you’re only seeing that person in one dimension,” she said.

Dealing with the Outside World

Sumner relayed a story about a time when she was out shopping with her son Charlie, who has Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome and cerebral palsy. When she saw two preteen boys laughing and whispering, she did what always does: She said hi. Charlie waved. But they didn’t wave back. They kept laughing. Their mom noticed but for some reason looked away.

“That threw me. You expect another grown-up to have your back,” Sumner said.

Next time she’s in a similar situation, she said she’ll try to draw in the adult from the outset. “I should’ve said, ‘Hi, ma’am. This is Charlie. What are your sons’ names?’” she said. Sumner also said she has to remind herself that her son typically isn’t as offended as she is.

Leach noted that his goal is “to make others feel comfortable to facilitate a positive interaction.”

“I’ll try to invite kids over that are curious. ‘This is the way Corbin eats and here’s why,’ ” he said.

The Birds and the Bees

Mshar admitted that she wishes she had brought up this topic earlier, given that she has two teenage sons with Down’s Syndrome who both love hugs – and the deep pressure they provide.

“People don’t want unsolicited hugs from 16-year-old boys,” she said.

She has used Social Stories to let them know when it’s appropriate to hug and when a fist bump or a handshake might be better. School social workers and psychologists have helped her put together those stories, which use images to teach appropriate behavior.

Mshar has also used hula hoops to explain the concept of personal space. And she reminds her kids about some of these lessons before they go out.

“It takes a lot of repetition,” she said.

Dr. Matheis noted that she has worked with special needs kids who’ve been confused by the changes their bodies go through during puberty. They need help understanding those changes and how to deal with them.

“They don’t always know that this is normal,” she said.